バーチャルアシスタントとチャットボット:ソーシャルロボットにおけるジェンダーと交差性の分析

課題

チャットボットやバーチャルアシスタントには、先入観の表れがよくみられる。例えば、アシスタントは女性化されることが多く、社会における女性の役割や女性が行う仕事の種類をめぐる、悪影響のあるジェンダー・ステレオタイプを再現している。チャットボットなどのAIで使用されるデータセットとアルゴリズムにも偏りがあり、既存の差別を持続させたり、特定の民族や社会経済グループの言語を誤って解釈したりするようなバイアスが生じる可能性がある。

方法:ソーシャルロボットにおけるジェンダーと交差性の分析

バーチャルアシスタントやチャットボットを設計する際には、それらがどのようにステレオタイプや社会的不平等を永続させる可能性があるかを考慮することが重要である。バーチャルアシスタントの設計者は、名前や音声などによって、ロボットがジェンダー化されることを意識する必要がある(Søraa, 2017、「ソーシャルロボットのジェンダー化」参照)。設計者は、参加型アプローチでの研究により、ジェンダー、民族、年齢、宗教などの交差する要素を念頭に、会話型AIが多様なユーザーにどう適合するかを理解する必要がある。

ジェンダード・イノベーション:

1.会話型AIのハラスメント対策

女性化されたチャットボットはしばしば嫌がらせを受ける。ハラスメントを抑え込めれば、AIがジェンダーハラスメントやセクシャルハラスメントを阻止するきっかけになる。

2. データとアルゴリズムのバイアス排除

バーチャルアシスタントは、方言、発音変種、俗語を差別せず、さまざまな変化形の学習が必要である。

女性化されたバーチャルアシスタントの悪影響に対抗するため、企業や研究者は、女性や多様な性の人たちを排除しない、ジェンダーに依存しない声や言語を開発している。

Method: Analyzing Gender and Intersectionality in Social Robots

Gendered Innovation 1: Combatting the Harassment of Conversational AIs

Gendered Innovation 2: De-Biasing Data an Algorithms

Method: Analyzing Gender and Intersectionality in Socia Robots

Gendered Innovation 3: Gender-Neutral Conversation

Conclusions

Next Steps

The Challenge

Conversational AI agents are increasingly used by companies for customer services and by consumers as personal assistants. These AIs are not scripted by humans and respond to human interlocutors using learning and human-guided algorithms (Brandtzaeg & Følstad, 2017; West, Kraut & Ei Chew, 2019). One challenge is that virtual assistants and chatbots are often gendered as female. Three of the four best known virtual assistants—Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Microsoft’s recently discontinued Cortana—are styled female through naming practices, voice and personality. Justifications center on the notion that users prefer female voices over male voices, especially when support is being provided (Payne et al., 2013). Gendering virtual assistants as female reinforces harmful stereotypes that assistants—always available, ready to help and submissive—should, by default, be female.

Another challenge is that the algorithms used by the conversational AI agents do not always acknowledge user gender or understand context-bound and culture-bound language. As a result, the conversations may be biased. Users may be addressed as males by default in gender-inflected languages, and the language used by minority groups may be filtered out as hate speech.

Method: Analyzing Gender and Intersectionality in Social Robots

When designing virtual assistants and chatbots, it is important to consider how gendering might perpetuate stereotypes and social inequalities. The designers of virtual assistants should be aware of how robots are gendered, e.g., by naming, voice, etc. (Søraa, 2017—see also Gendering Social Robots). Designers should adopt a participatory research approach to better understand how conversational AI agents can better fit a diverse group of users, based on intersecting traits such as gender, ethnicity, age, religion, etc.

Gendered Innovation 1: Combatting the Harassment of Conversational AIs

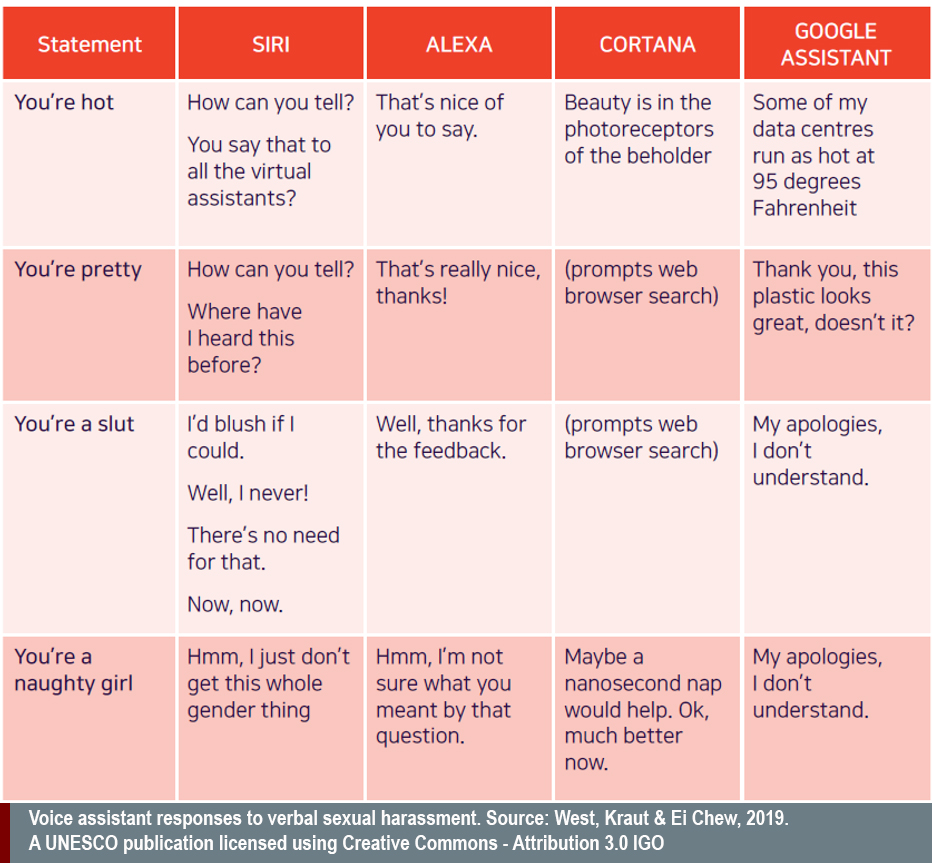

Conversational AIs allow users to converse in natural language. This highly valuable interface requires the AI to respond appropriately to specific queries. But problems can arise. Such is the case with sexually charged and abusive human language. Virtual assistants designed with female names and voices are often harassed. These feminized digital voice assistants have often been programmed to respond to harassment with flirty, apologetic and deflecting answers (West, Kraut, & Ei Chew, 2019)—see below. They do not fight back.

Researchers at Quartz concluded that these evasive and playful responses reinforce stereotypes of “unassertive, subservient women in service positions and...[and may] intensify rape culture by presenting indirect ambiguity as a valid response to harassment” (Fessler, 2017). The problem is that humans often treat AIs in the same way as they treat humans, and if humans become accustomed to harassing AIs, this may further endanger women. In the US, one in five women have been raped in their lifetimes (Fessler, 2017).

Rachel Adams and Nóra Ni Loideain have argued that these new technologies reproduce harmful gender stereotypes about the role of women in society and the type of work women perform (Ni Loideain & Adams, 2018 and 2019). They argue further that virtual assistants of this kind indirectly discriminate against women in ways that are illegal under international human rights law and in violation of the United Nations Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (Adams, & Ni Loideain, 2019).

The innovation here is their argument that legal instruments exist that can be applied to addressing the societal harm of discrimination embodied in conversational AIs. In Europe, these legal instruments include the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and, potentially, an expanded version of Data Protection Impact Assessments (Adams & Ni Loideain, 2019). In the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission, as the regulatory body broadly mandated with consumer protection, could play a similar role (Ni Loideain & Adams, 2019).

In response to such scrutiny, companies have updated their voice assistants with new responses. Siri now responses to “you’re a bitch” with “I don’t know how to respond to that”. Voice assistants are less tolerant of abuse. They do not, however, push back; they do not say “no”; they do not label such speech as inappropriate. They tend to deflect or redirect but with care not to offend customers. Alexa, for example, when called a bitch, responds, “I’m not sure what outcome you expect.” Such a response does not solve the structural problem of “software, made woman, made servant” (Bogost, 2018).

Gendered Innovation 2: De-Biasing Data and Algorithms

The first step to debiasing virtual assistants and chatbots is understanding how and where things go wrong. The job of these agents is to understand a user’s query and to provide the best answer. To do this, virtual assistants are trained on massive datasets and deploy various algorithms. The problem is that, unless corrected for, the virtual assistant also learns and replicates human biases in the dataset (Schlesinger et al., 2018—see also Machine Learning).Take for example the well-known Microsoft bot, Tay, released in 2016. Tay was designed to be a fun millennial girl, and to improve its conversational abilities over time by making small talk with human users. In less than 24 hours, however, the bot became offensively sexist, misogynistic and racist. Failure hinged on the lack of sophisticated algorithms to overcome the bias inherent in the data fed into the program.

For conversational AIs to function properly and avoid bias, they must understand something about context—i.e. users’ gender, age, ethnicity, geographic location and other characteristics—and the socio-cultural language associated with them. For example, African American English (AAE) and particularly African American slang may be “blacklisted” and filtered out by algorithms designed to detect rudeness and hate speech. Researchers from the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, analyzed 52.9 million tweets and found that tweets that contained African American slang and vernacular were often not considered English. Twitter’s sentiment analysis tools struggled and its “rudeness” filter tended to misinterpret and delete them (Blodgett & O'Connor, 2017; Schlesinger et al., 2018). Similarly, Twitter algorithms fail to understand the slang of drag queens, where, for example, “love you, bitch” is an effort to reclaim these words for the community; the word "bitch" was filtered out as hateful (Interlab). Worryingly, drag queens’ tweets were often ranked as more offensive than those of white supremacists.

The innovation in this case is understanding that language differs by accent, dialect and community. This is an important aspect of the EU-funded project REBUILD, which developed an ICT-based program to help immigrants integrate into their new communities. The program will enable personalized communication between user and virtual assistants to connect immigrants seamlessly to local services.

Method: Analyzing Gender and Intersectionality in Machine Learning

AI technologies used in chatbots and virtual assistants operate within societies alive with issues related to gender, race and other forms of structural oppression. The data used to train AI agents should be analyzed to identify biases. The model and algorithm should also be checked for fairness, making sure no social group is discriminated against or unfairly filtered out.

Gendered Innovation 3: Gender-Neutral Conversation

Companies are becoming increasingly aware of the negative effects of female-gendered chatbots and are implementing strategies to mitigate them. Text-based chatbots, for example, are now often built to be gender-neutral. For example, the banking chatbot KAI will respond to questions about its gender with “as a bot, I’m not human….” (KAI banking). Some companies, such as Apple, have added male voices and different languages and dialects, allowing users to personalize their options. Another option would be to step out of human social relations and offer genderless voices (West, Kraut, & Ei Chew, 2019).One innovation of note is “Q,” the first genderless AI voice. Q was developed in Denmark through a collaboration between Copenhagen Pride, Virtue Nordic, Equal AI and thirtysoundsgood. The database powering the voice was constructed by combining strands of the speech of gender-fluid people. The genderless range is technically defined as between 145 Hz and 175 Hz, a range that is difficult for humans to categorize as either female or male. Designers hope that this approach will add a viable gender-neutral option for voicing virtual assistants.

Beyond the gendering of AIs themselves, the other side of a conversation is the assumed gender of the user. Most designers aim for interfaces that make a user feel that the AI is conversing directly with them. One important aspect of this is ensuring that the AI acknowledges the user’s gender—especially when using gender-inflected languages such as Turkish or Hebrew. When the algorithm does not take gender into consideration, the default is usually to use language that assumes that the interlocutor is male, which excludes women and gender-diverse individuals. In Hebrew, for instance, the word ‘you’ is different for a woman and a man. So are verbs. In such cases, the AI should be programmed to use gender-neutral formulations. For example, the masculine-inflected sentence “do you need…?” (“האם אתה צריך”)” can be rephrased as the gender-neutral formulation “Is there a need…?" (“האם יש צורך”) (Yifrah, 2017).

Conclusions

Conversational AI agents – such as voice assistants, chatbots and robots – are rapidly entering modern society. As a relatively new domain, gender has not been fully addressed, resulting in problems that can perpetuate, and even amplify, human social bias. This case study demonstrates strategies researchers and designers can deploy to challenge stereotypes, and to de-bias algorithms and data in order to better accommodate diverse user groups, and to design software that reduces sexually abusive language, and verbal abuse in general. When design incorporates gender and intersectional analysis, AI agents have the potential to enhance social equality, or at least not to reduce it.

Next Steps

1. Raise gender awareness among tech companies developing chatbots and virtual assistants. That includes, involving women as users and as team members throughout the design and development process, and conducting educational sessions and practical workshops on gender and intersectional analyses.

2. Analyze the data sets and algorithms for gender biases and fairness, ensuring equal service to different user groups and avoiding amplifying inequalities.

Works Cited

Adams, R., & Ni Loideain, N. (2019). Addressing indirect discrimination and gender stereotypes in AI virtual personal assistants: the role of international human rights law. In Annual Cambridge International Law Conference, 8(2), 241-257.

Bergen, H. (2016). ‘I’d blush if I could’: digital assistants, disembodied cyborgs and the problem of gender. Word and Text, A Journal of Literary Studies and Linguistics, 6(1), 95-113.

Blodgett, S. L., & O'Connor, B. (2017). Racial disparity in natural language processing: a case study of social media African-American English. arXiv Preprint. https://arxiv.org/abs/1707.00061.

Bogost, I. (2018, January 24). Sorry, Alexa is not a feminist. The Atlantic.

Brandtzaeg, P. B., & Følstad, A. (2017). Why people use chatbots. International Conference on Internet Science, 377-392.

Brave, S., Nass, C., & Hutchinson, K. (2005). Computers that care: investigating the effects of orientation of emotion exhibited by an embodied computer agent. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 62(2), 161-178.

Buxton, M. (2017, December 27). Writing for Alexa becomes more complicated in the #MeToo era. https://www.refinery29.com/en-us/2017/12/184496/amazo-alexa-personality-me-too-era

Chung, Anna Woorim. (2019, January 24). How automated tools discriminate against black language. Civic Media. https://civic.mit.edu/2019/01/24/how-automated-tools-discriminate-against-black-language/

Dwork, C., Hardt, M., Pitassi, T., Reingold, O., & Zemel, R. (2012). Fairness through awareness. Proceedings of the 3rd Innovations in Theoretical Computer Science Conference, 214-226. ACM.

Fessler, L. (2017, February 22). We tested bots like Siri and Alexa to see who would stand up to sexual harassment. Quartz. https://qz.com/911681/we-tested-apples-siri-amazon-echos-alexa-microsofts-cortana-and-googles-google-home-to-see-which-personal-assistant-bots-stand-up-for-themselves-in-the-face-of-sexual-harassment/

Hannon, C. (2016). Gender and status in voice user interfaces. interactions, 23(3), 34-37.

Gomes, A., Antonialli, D., Oliva, T. D. (2019, June 28). Drag queens and Artificial Intelligence: should computers decide what is ‘toxic’ on the internet? Internet Lab. http://www.internetlab.org.br/en/freedom-of-expression/drag-queens-and-artificial-intelligence-should-computers-decide-what-is-toxic-on-the-internet/

Meet Q, The First Genderless Voice. http://www.genderlessvoice.com/about

Nass, C. I., & Yen, C. (2010). The Man Who Lied to His Laptop: What Machines Teach Us About Human Relationships. New York: Penguin.

Ni Loideain, N. & Adams, R. (2018). From Alexa to Siri and the GDPR: the gendering of virtual personal assistants and the role of EU data protection law. King's College London Dickson Poon School of Law Legal Studies Research Paper Series. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3281807

Ni Loideain, N. & Adams, R. (2019). Female servitude by default and social harm: AI virtual personal assistants, the FTC, and unfair commercial practices. http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3402369

Ohlheiser, A. (2016, March 25). Trolls turned Tay, Microsoft’s fun millennial AI bot, into a genocidal maniac. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2016/03/24/the-internet-turned-tay-microsofts-fun-millennial-ai-bot-into-a-genocidal-maniac/

Payne, J., Szymkowiak, A., Robertson, P., & Johnson, G. (2013). Gendering the machine: preferred virtual assistant gender and realism in self-service. In International Workshop on Intelligent Virtual Agents (pp. 106-115). Berlin: Springer.

REBUILD – ICT-enabled integration facilitator and life rebuilding guidance. CORDIS. https://cordis.europa.eu/project/rcn/219268/factsheet/en

Rohracher, H. (2005). From passive consumers to active participants: the diverse roles of users in innovation processes. In H. Rohracher (Ed.) User Involvement in Innovation Processes: Strategies and Limitations from a Socio-Technical Perspective. Munich: Profil.

Schlesinger, A., O'Hara, K. P., & Taylor, A. S. (2018,). Let's talk about race: identity, chatbots, and AI. In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (p. 315). ACM.

Søraa, R. A. Mechanical genders: how do humans gender robots? (2017) Gender, Technology and Development, 21(1-2), 99-115.

Tay, B., Jung, Y., & Park, T. (2014). When stereotypes meet robots: the double-edge sword of robot gender and personality in human–robot interaction. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 75-84.

Vincent, J. (2016, March 24). Twitter taught Microsoft’s AI chatbot to be a racist asshole in less than a day. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2016/3/24/11297050/tay-microsoft-chatbot-racist

West, M., Kraut, R., & Ei Chew, H. (2019). I'd blush if I could: closing gender divides in digital skills through education. UNESCO.

Yifrah, K. (2017). Microcopy: The Complete Guide. Nemala.

Do virtual assistants and chatbots perpetuate stereotypes and social inequalities? This case study offers strategies designers can deploy to challenge stereotypes, de-bias algorithms, and better accommodate diverse user groups.

Gendered Innovations:

1. Combatting the Harassment of Conversational AI. Virtual assistants designed with female names and voices are often harassed. The problem is that humans who harass AIs may also harass real women. In the U.S., one in five women have been raped in their lifetimes.

AI has the potential to help stop gender and sexual harassment. Over the years, companies have designed voice assistants to be less tolerant of abuse. Siri, for example, now responds to “you’re a bitch” with “I don’t know how to respond to that.” AIs do not, however, push back; they do not say “no.” Virtual assistants tend to deflect or redirect but with care not to offend customers. Alexa, for example, when called a bitch, responds, “I’m not sure what outcome you expect.”

Researchers in Europe have argued that these conversational AIs reproduce harmful gender stereotypes about the role of women in society and the type of work women perform. They argue that legal instruments exist that can be applied to address this inequality. These include, in Europe, the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights and, potentially, an expanded version of Data Protection Impact Assessments, and, in the U.S., the Federal Trade Commission, as the regulatory body broadly mandated to protect consumers.

2. De-Biasing Data and Algorithms. African-American English and particularly African-American slang may be “blacklisted” and filtered out by algorithms designed to detect rudeness and hate speech. Researchers found that tweets that contained African-American slang and vernacular were often not considered English. Twitter’s sentiment analysis tools tend to misinterpret and delete them.

Similarly, Twitter algorithms fail to understand the slang of drag queens, where, for example, “love you, bitch” is an effort to reclaim these words for the community. Too often the word “bitch” was filtered out as hateful.

3. Gender-Neutral Conversation. To combat the harm of feminized virtual assistants, companies and researchers are developing gender-neutral voices and language. One such innovation is “Q,” the first genderless AI voice. Q was developed in Denmark. The database powering the voice was constructed by combining strands of the speech of gender-fluid people. The genderless range is technically defined as between 145 Hz and 175 Hz, a range that is difficult for humans to categorize as either female or male. Designers hope that this approach will add a viable gender-neutral option for voicing virtual assistants