COVID19/新型コロナウイルス感染症:セックスの分析とジェンダーの分析

課題

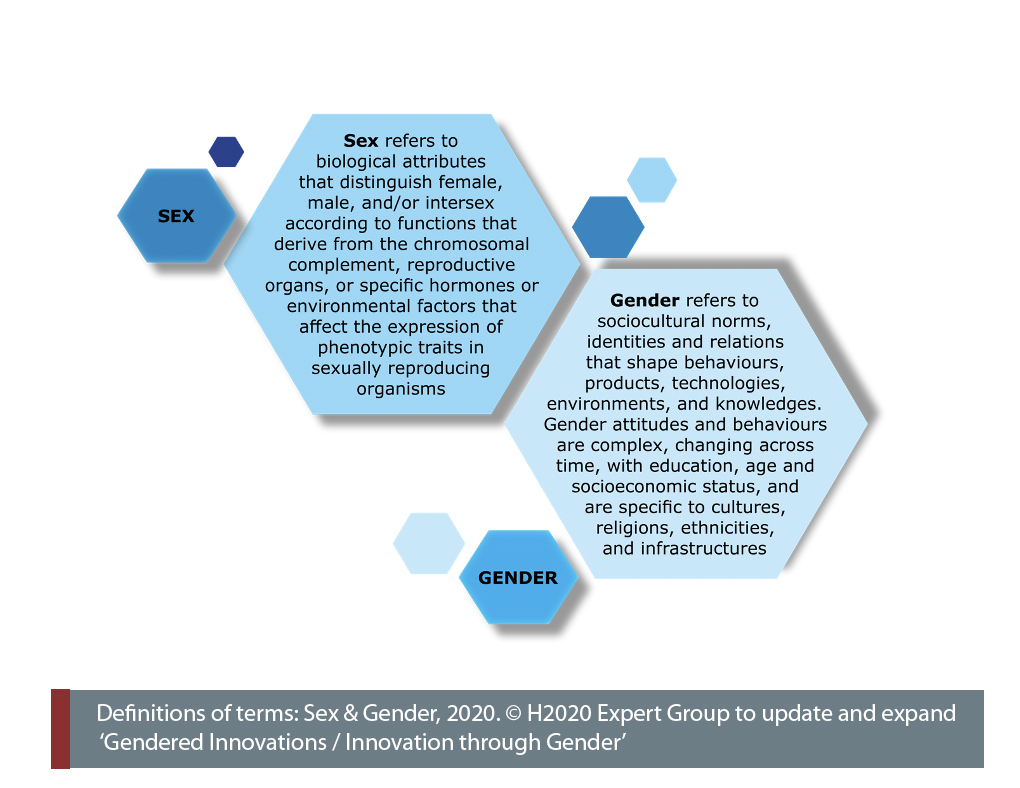

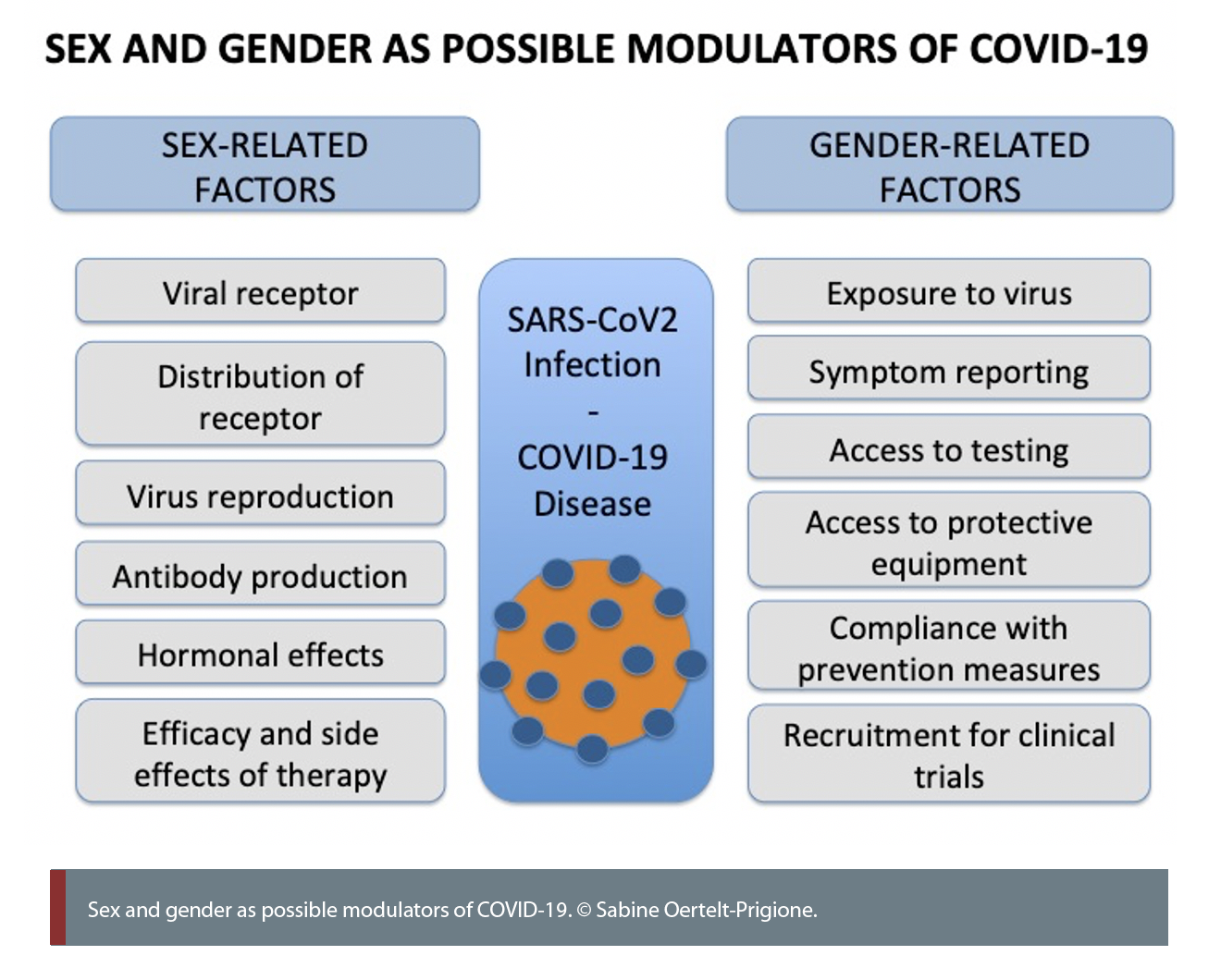

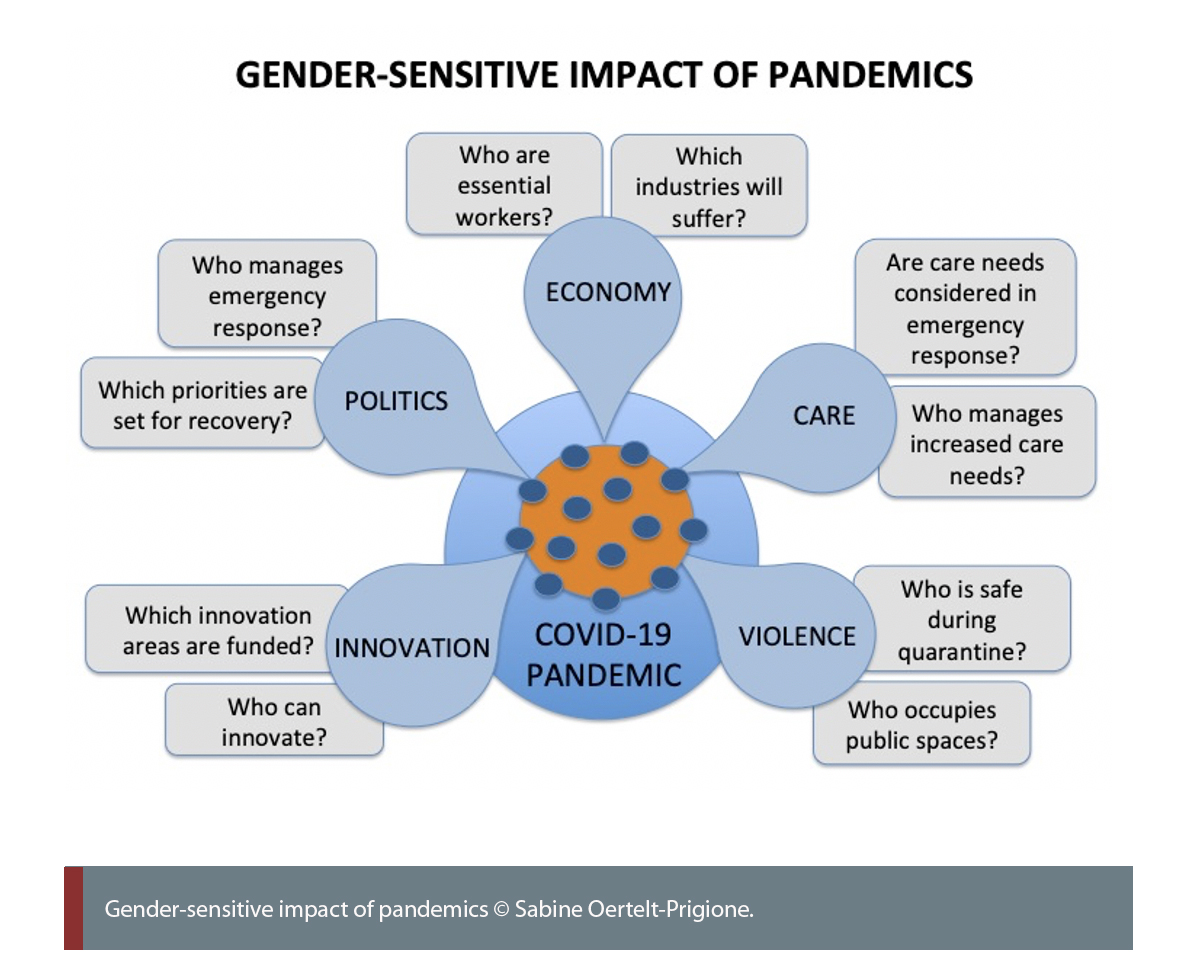

感染症には誰もがかかる可能性があるが、セックス(生物学的な性)やジェンダー(社会文化的な性)は人体の免疫反応や病気の経過に影響を与える可能性がある。パンデミックの生理的影響は、医療や経済・物流資源の制限など、より広範な社会的・制度的課題と交差している。COVID-19(新型コロナウイルス感染症)に関する現在の世界的な統計によると、急性感染の死者数は女性よりも男性の方が多く、一方、パンデミックの健康、経済、社会への影響に関しては、男性よりも女性の方が長期的に被害を受けると予測されている。経済活動の再開戦略、製品開発、AIソリューションなど、健康面以外の革新的なソリューションにも、セックスとジェンダーを考慮する必要がある。

方法:セックス分析

COVID-19の罹患率と死亡率に関連するすべてのデータは、性別ごとに集計する必要がある。女性は、重症急性呼吸器症候群コロナウイルス-2(SARS-CoV 2)などのウイルスとの接触に対して、自然感染とワクチン接種の両方を通してより強く反応するとされている。このような性差は、診断や治療において考慮される必要がある。COVID-19の研究では、創薬や前臨床研究で男性と女性の細胞を使用し、実験動物もオスとメスを使い、臨床試験には女性と男性の両方に参加してもらうなど、両性での研究が必要である。女性は男性よりも副作用を発症する割合が高いため、すべての医薬品およびワクチンの治験には性差分析を含める必要がある。

方法: ジェンダー分析

予防対策は、ジェンダーを考慮して設計すべきである。女性の方が手指衛生を遵守していると報告されている。ジェンダーは、労働と家庭内のケアの分担に影響を与える。女性は医療分野など感染リスクの高い職業に就くことが多く、病気の家族の世話をすることも多い。予防用品、治療、金銭的支援の配分は、男女平等でなくてはならない。デジタルリソースによる予防対策を開発する際にも、ジェンダーを考慮した設計が必要である。

ジェンダード・イノベーション:

1. 免疫反応の性差を研究する ことで、男性のほうが女性よりもCOVID-19による死亡率が高いという課題に対処できる可能性がある。

2. ワクチンおよび治療薬の投与量と副作用の性差に着目する ことは、SARS-CoV2感染症やCOVID-19に対する治療法の開発に必須である。

3. ジェンダー別にリスク因子を分析 することで、長期的に女性の死亡率を低減できる可能性がある。EUでは、医療従事者の76%が女性である。このため、女性のほうがウイルスにさらされる可能性が非常に高くなる。そのため、個人用の防護用品が必要になる。

4. ジェンダーに配慮した予防キャンペーンを設計することで、コンプライアンスを向上させ、ウイルスとの接触を減らすことができる。効果的な公衆衛生キャンペーンのためには、予防対策、デジタルプラットフォーム、ウェアラブル機器を使ったデータ収集、AI予測モデルを、性別ごとの傾向を分析して配備する必要がある。

5. ジェンダー別の公共安全対策における社会経済的負担を考慮 することで、影響の不平等を緩和することができる。公衆衛生上の緊急事態は、ジェンダー分業の崩壊をもたらす可能性がある。女性や多様な性の人々は、経済的な不安、差別、ジェンダーにもとづく暴力を経験するリスクが著しく高い。

COVID-19: Analyzing Sex & Analyzing Gender

This case study was first released 28 May 2020, and is also available as a PDF here.

The Challenge

Although infectious diseases can affect everyone, sex and gender can significantly impact immune responses and the course of the disease in the human body. Importantly, the biological impacts of the pandemic intersect with broader social and systemic challenges, such as limited healthcare, and economic and logistic resources. In the case of COVID-19, current worldwide statistics show more men than women dying of acute infection (GlobalHealth5050, 2020), while women are projected to suffer more than men from the health, economic and social consequences of the pandemic in the long term. Innovative solutions beyond health, such as economic re-entry strategies, product development and AI solutions, also need to consider sex and gender.

Gendered Innovation 1: Studying Sex Differences in Immune Responses

Sex differences in immune responses have been reported in infectious diseases, autoimmunity and inflammation. Females appear to respond more vigorously to viral infections and produce more antibodies in response to infection and vaccination (Klein & Flanagan, 2016).The mechanisms leading to these differences can be hormonal (i.e. the different effects of testosterone, oestrogens or progesterone), genetic (biological females have two X chromosomes while males have only one) or related to differences in intestinal bacteria.

A more vigorous immune response may induce a higher risk of autoimmune disease in females, but also a better capacity to fight infection. Initial studies report a higher production of certain subtypes of antibodies, called IgGs, in females than in males after infection with SARS-CoV2 (Zeng et al., 2020).

These differences might be relevant to the sensitivity and specificity of serological tests. The receptor used by the virus to infect host cells is the ACE2 receptor. This molecule is encoded on the X chromosome and influenced by oestrogens and androgens circulating in the body (Bukowska et al., 2017).

This means that responses to the virus and to therapies may vary, especially for groups undergoing hormonal therapies, either after menopause or to align their physical appearance with their gender identity. The possible influence of oestrogens and progesterone on the body’s response to COVID-19 in people of any gender is currently being investigated in two small trials in the United States (NCT04359329 and NCT04365127).

Gendered Innovation 2: Focusing on Dosing and Sex-Specific Side Effects of Vaccines and Therapeutics

Women appear to experience a higher overall incidence of medication side effects than men. This might be related to biological differences, differences in therapeutic choices or differences in reporting (see Case Study: Prescription Drugs). Potential sex differences in response to and the efficacy of novel therapies and vaccines need to be taken into account (Tannenbaum et al., 2017). Different doses of vaccine may be needed for females and males, and side effects may occur at different rates.

For example, females are at higher risk of developing irregularities in heart rhythm (QT prolongation) due to physiological differences in the heartbeat (see Case Study: Heart Disease in Diverse Populations). This risk increases with the use of heart medication and many other therapies, such as hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin, currently being tested for use against COVID-19.

In addition, sex-specific issues, such as the provision of potentially life-saving therapies to pregnant women while preventing fetal complications, need to be considered in the design of clinical trials. This is particularly relevant in countries with limited healthcare resources, and where fertility rates might be higher, thus significantly increasing the numbers of potentially pregnant COVID-19 patients.

The Horizon 2020 project i-CONSENT investigates the intersection of the gender dimension and ethics in informed consent. It addresses the relationship between ethics and safety when people are participating in clinical trials, including co-decision-making between partners and the impact of self-determination and power (Persampieri, 2019).

Method: Analyzing Sex

All data related to COVID-19 morbidity and mortality should be disaggregated by sex (Wenham et al., 2020). Females generally respond more intensely to contact with viruses such as SARS-CoV2, including both natural infection and vaccination (Klein & Flanagan, 2016), and the potential impacts of these differences should be considered in:

All study of COVID-19 needs to integrate sex as a biological variable. This includes using female and male cells and experimental animals in drug discovery and development and in preclinical research, as well as using women and men in clinical trials. Females develop side effects to medications more frequently than males (Obias-Manno et al., 2007), and all drug and vaccine trials for COVID-19 should include sex-specific analyses.

- • identifying and reporting symptoms,

- • developing diagnostics and testing,

- • validating therapeutics.

Gendered Innovation 3: Consider Gender-Specific Risk Factors

Worldwide, women are more frequently employed in service professions, including healthcare. According to the European Institute of Gender Equality, women represent 76 % of the 49 million healthcare workers in the EU (European Institute of Gender Equality). Care professionals in hospitals, nursing homes and the community come into contact with the virus much more frequently than the general population. They are exposed to large numbers of SARS-CoV2 patients and may be exposed to higher concentrations of the virus (Liu et al., 2020). Women also perform the majority of caring duties in families and immediate communities.

Professional and private risks need to be factored into public health strategies. Healthcare workers are preferentially tested for SARS-CoV2, but is equitable access provided for informal caregivers and healthcare workers outside of hospitals? Is gender-sensitive budgeting applied in allocating emergency resources? Is personal protective equipment provided fairly to all individuals at comparable risk in healthcare institutions?

In addition to healthcare professionals, cleaning personnel and janitorial staff tend to be overexposed to the virus and require protective equipment. When developing personal protective equipment, anatomical differences need to be analyzed to ensure proper fit and to avoid ergonomic difficulties (Sutton, Irvin et al., 2014); gender-specific user preferences should also be considered (Tannenbaum et al., 2019).

An example of how an acute situation like the COVID-19 pandemic can be integrated into ongoing structural gender-mainstreaming activities is provided by the Horizon 2020 project ACT. ACT has developed a platform for communities of practice on gender equality in research organizations and has recently used its platform to host webinars offering insight into the gender dimensions of research funded on the pandemic.

Gendered Innovation 4: Design Gender-Sensitive Prevention Campaigns

Public health strategies to contain the spread of SARS-CoV2 include containing coughing and sneezing, social/physical distancing and frequent hand washing. Gender differences in the uptake of hand hygiene have been reported in the past and these findings should be incorporated into the design of preventative SARS-CoV2/COVID-19 campaigns.

Women in the general population wash their hands more frequently than men after using a bathroom (Borchgrevink et al., 2013) and women healthcare workers wash their hands more often than their male colleagues (Szilagyi et al., 2013). When investigating the gender-specific incentives for hand washing, it appears that women respond more to knowledge-based approaches (Suen et al., 2019), while men respond more to disgust (Judah et al., 2009). This means that innovations are required to engage men in more active hand washing.

For effective public health campaigns, gender-specific preferences should be analyzed and deployed in digital platforms, data collection wearables and artificial intelligence prediction models.

Gender differences are not just relevant for disease-specific prevention, but also for the management of general risk factors, such as smoking, obesity and diabetes. Smoking has been reported as a significant risk factor for severe COVID-19 disease (Guan et al., 2020) and is more common in men worldwide, although this difference is reducing in some countries.

Method: Analyzing Gender

Preventative measures should be designed in a gender-sensitive manner to reach everyone in the community. Women reportedly comply more with hand hygiene guidelines (Borchgrevink et al., 2013), and incentives to encourage such preventative behaviors should be gender-sensitive (Judah et al., 2009).

Gender affects the division of labour and care duties in families and communities. Women are more frequently employed in professions with a high risk of infection, such as healthcare, and are more frequently responsible for the care of sick family members (International Labour Organization, 2016).

The design of personal protective equipment needs to take anatomical differences into consideration as well as users’ gendered preferences. The allocation of protective equipment, therapies and financial aid should be gender-equitable. Finally, gender-sensitive design should be employed when developing digital platforms for preventative measures.

Gendered Innovation 5: Considering the Gender-Specific Socioeconomic Burden of Public Safety Measures

Limiting physical contact is important in pandemics involving viral and bacterial agents that are transmitted person-to-person. A highly transmittable airborne virus, such as SARS-CoV2, has led to social/physical distancing measures and quarantines in many parts of the world. In most parts of the world, women are more likely than men to be non-salaried employees or self-employed. They also are more likely to work in the service industries, such as care, wellness, cleaning and food handling (International Labour Organization, 2016).

The enforced closure of the service industry during quarantine has impacted the non-traditional workforce in two distinct ways: “non-essential” workers lose their jobs, leaving individuals dependent on economic support from partners, families and the state; “essential” workers are required to continue their activities under significant physical and psychological stress. Both scenarios have the potential to shift established gender roles and to lead to a surge in stress, existential fears and violence in public and domestic settings (van Gelder et al., 2020). Understanding and empathising with potential survivors is an essential aspect of prevention that has been addressed innovatively in the Horizon 2020 project VRespect.Me, which developed a training app using virtual reality to place perpetrators of domestic violence in the position of victims (Seinfeld et al., 2018).

Socioeconomic measures also harbour the potential to exacerbate existing inequalities. The design of solutions should be intersectional (see Method: Intersectional Approaches), including dimensions such as social origin and ethnicity/migration, among others. The European Research Council project GENDERMACRO investigated the complex interconnections between female empowerment and household economics. Simply providing resources to a female household member might lead to unexpected negative consequences if gender dynamics, such as power relations, role assumptions and priorities, are not taken into account (Doepke & Tertilt, 2011). These findings are essential for the development of gender-sensitive policies to improve the economic situation for all household members, especially in times of crisis such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Service restrictions affect many domains in a gendered manner, but are especially relevant in healthcare. Emergency departments worldwide are reporting a reduction in demand not related to COVID-19, sparking concerns about the potential lack of treatment of medical emergencies, such as heart attack and strokes (Tam et al., 2020). Routine reproductive healthcare might also suffer. Political decisions taken on health priorities in several countries have already affected access to contraception as well as to medically assisted reproduction and safe abortions.

Conclusions

The SARS-CoV2/COVID-19 pandemic highlights the urgent need to incorporate sex and gender analysis into research and innovation processes. More men than women appear to die of the disease, but women are more frequently employed in high-risk jobs and disproportionately responsible for caring for those who are unwell. Sex differences in immunology and response to therapies can help elucidate disease-specific pathways, which could benefit everyone. Considering the gender dimensions of the pandemic could help mitigate the acute and long-term inequities that stem from its socioeconomic consequences.

Next Steps for SARS-CoV2/COVID-19 National and EU funded Research:

Sex as a biological variable needs to be integrated into research on SARS-CoV2 infection patterns, the development of the disease and COVID-19 treatments. COVID-19 pathology demonstrates sex differences in host susceptibility and clinical course. Including sex analysis in all reporting can offer new insights for the development of targeted therapies.

Sex needs to be recorded in all COVID-19 clinical trials. This should not be limited to balanced participant rates but, most importantly, should include sex-disaggregated reporting of response, side effects, dosage adaptations and long-term effects.

Approaches to prevention should be gender-sensitive to ensure broad adoption. SARS-CoV2 is projected to circulate in the general population for some time, and there is currently uncertainty about the extent and duration of immunity. Preventative measures, such as hand washing and the mandatory wearing of masks, should be implemented in a gender-sensitive fashion, and personal protective equipment used should be designed for a range of users. The development of digital preventative solutions should focus on gender preferences and barriers. Aspects relating to domestic and gender-based violence have been highlighted in the recent EUvsVirus hackathon and tandem Move It Forward for Women vs. COVID19 hackathon.

The gender dimensions of the outbreak in terms of unemployment, care duties and associated social inequity need to be considered for long-term management of the disease and for economic re-entry strategies. Gender impact assessments (see Method: Gender Impact Assessment) of proposed policies should be conducted. Adequate access to social, economic and health services needs to be ensured for all.

Works Cited

Borchgrevink, C. P., J. Cha & Kim, S. (2013), ‘Hand washing practices in a college town environment’, Journal of Environmental Health, 75(8), 18–24.

Bukowska, A., L. Spiller, C. Wolke, U. Lendeckel, S. Weinert, J. Hoffmann, P.

Bornfleth, I. Kutschka, A. Gardemann, B. Isermann & Goette, A. (2017). ‘Protective regulation of the ACE2/ACE gene expression by estrogen in human atrial tissue from elderly men’. Experimental Biology and Medicine (Maywood), 242(14), 1412–1423.

Doepke, M. & Tertilt, M. (2011). ‘Does Female Empowerment Promote Economic Development?’, Policy Research Working Paper – World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/1813-9450-5714

European Institute for Gender Equality. Frontline Workers (https://eige.europa.eu/covid-19-and-gender-equality/frontline-workers). GlobalHealth5050. (2020) (https://globalhealth5050.org/).

Guan, W. J., Z. Y. Ni, Y. Hu, W. H. Liang, C. Q. Ou, J. X. He, L. Liu, H. Shan, C. L. Lei, D. S. C. Hui, B. Du, L. J. Li, G. Zeng, K. Y. Yuen, R. C. Chen, C. L. Tang, T. Wang, P. Y. Chen, J. Xiang, S. Y. Li, J. L. Wang, Z. J. Liang, Y. X. Peng, L. Wei, Y. Liu, Y. H. Hu, P. Peng, J. M. Wang, J. Y. Liu, Z. Chen, G. Li, Z. J. Zheng, S. Q. Qiu, J. Luo, C. J. Ye, S. Y. Zhu, & Zhong, N. S., for the China Medical Treatment Expert Group (2020). ‘Clinical Characteristics of Coronavirus Disease 2019 in China’, New England Journal of Medicine, 382(18), 1708–1720.

International Labour Organization (2016). ‘Women at Work’,(https://www.ilo.org/gender/Informationresources/Publications/WCMS_457317/lang–en/index.htm).

Judah, G., R. Aunger, W. P. Schmidt, S. Michie, S. Granger & Curtis, V. (2009). ‘Experimental pretesting of hand-washing interventions in a natural setting’, American Journal of Public Health, 99 Suppl 2, S405–411.

Klein, S. L. & Flanagan, K. L. (2016).‘Sex differences in immune responses’, Nature Reviews Immunology, 16(10), 626–638.

Liu, Y., L. M. Yan, L. Wan, T. X. Xiang, A. Le, J. M. Liu, M. Peiris, L. L. M. Poon & Zhang, W. (2020). ‘Viral dynamics in mild and severe cases of COVID-19’, Lancet Infectious Diseases, 20, 656-657.

Obias-Manno, D., P. E. Scott, J. Kaczmarczyk, M. Miller, E. Pinnow, L. Lee-Bishop, M. Jones-London, K. Chapman, D. Kallgren & Uhl, K. (2007). ‘The Food and Drug Administration Office of Women’s Health: Impact of science on regulatory policy’, Journal of Womens Health, 16(6), 807–817.

Persampieri, L. (2019). ‘Gender and informed consent in clinical research: Beyond ethical challenges’, BioLaw Journal – Rivista di Biodiritto, (1), 65–87.

Seinfeld, S., J. Arroyo-Palacios, G. Iruretagoyena, R. Hortensius, L. E. Zapata, D. Borland, B. de Gelder, M. Slater & Sanchez-Vives, M. V. (2018). ‘Offenders become the victim in virtual reality: Impact of changing perspective in domestic violence’, Scientific Reports, 8(1), 2692.

Suen, L. K. P., Z. Y. Y. So, S. K. W. Yeung, K. Y. K. Lo & Lam, S. C. (2019). Epidemiological investigation on hand hygiene knowledge and behaviour: A cross-sectional study on gender disparity. e, 19(1), 401.

Sutton, E., M. Irvin, C. Zeigler, G. Lee & Park, A. (2014). ‘The ergonomics of women in surgery’, Surgical Endoscopy, 28(4), 1051–1055.

Szilagyi, L., T. Haidegger, A. Lehotsky, M. Nagy, E. A. Csonka, X. Sun, K. L. Ooi & Fisher, D. (2013), ‘A large-scale assessment of hand hygiene quality and the effectiveness of the WHO 6-steps. BMC Infectious Disease, 13, 249.

Tam, C. F., K. S. Cheung, S. Lam, A. Wong, A. Yung, M. Sze, Y. M. Lam, C. Chan, T. C. Tsang, M. Tsui, H. F. Tse & Siu, C. W. (2020). ‘Impact of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Outbreak on ST-Segment-Elevation Myocardial Infarction Care in Hong Kong, China’, Circulation: Cardiovascular Quality and Outcomes, 13(4), e006631.

Tannenbaum, C., D. Day & A. Matera (2017), ‘Age and sex in drug development and testing for adults’, Pharmacological Research, 121, 83–93.

Tannenbaum, C., R. P. Ellis, F. Eyssel, J. Zou & L. Schiebinger (2019). ‘Sex and gender analysis improves science and engineering’, Nature, 575(7781), 137–146.

van Gelder, N., A. Peterman, A. Potts, M. O’Donnell, K. Thompson, N. Shah, & Oertelt-Prigione, S. for the Gender and COVID-19 Working Group (2020). ‘COVID-19: Reducing the risk of infection might increase the risk of intimate partner violence’, EClinicalMedicine, 10348.

Wenham, C., J. Smith, R. Morgan, Gender and C.-W. Group (2020). ‘COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak’, Lancet, 395(10227), 846–848.

Zeng, F., C. Dai, P. Cai, J. Wang, L. Xu, J. Li, G. Hu & L. Wang (2020). ‘A comparison study of SARS-CoV-2 IgG antibody between male and female COVID-19 patients: A possible reason underlying different outcome between gender’, medRxiv, https://www.medrxiv.org/content/10.1101/2020.03.26.20040709v1

COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the urgent need to incorporate sex and gender analysis into research.

Sex and gender differences can influence the body’s immune response (see chart). Biologically, females appear to produce more antibodies in response to infection or vaccination. The reasons may be hormonal, genetic, or related to differences in intestinal bacteria. The body's response may also vary in people undergoing hormonal therapy, either after menopause or to align their physical appearance with their gender identity.

Gendered attitudes and behaviors also play a role. For example, smoking rates (higher in men), preventive measures such as hand washing (lower in men), and healthcare seeking (delayed in men) all contribute to higher risk in men.

Next Steps for SARS-CoV2/COVID-19 Research

- 1. Sex as a biological variable needs to be integrated into research on SARS-CoV2 infection patterns, the development of the disease, and COVID-19 treatments.

- 2. Sex needs to be recorded and analyzed in all COVID-19 clinical trials.

- 3. Approaches to prevention should be gender-sensitive to ensure broad adoption. Digital preventive solutions should focus on gender preferences and barriers.

- 4. The gender differences in terms of unemployment, care duties, and social inequities need to be considered for long-term management of the disease and for economic re-entry strategies.